“Or otherwise having substantive control” – what does it mean?

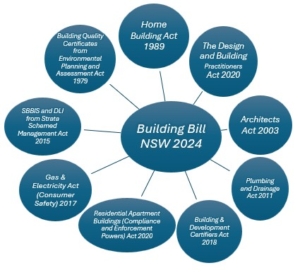

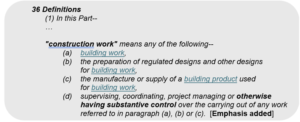

The phrase “otherwise having substantive control” is a critical legal concept under the Design and Building Practitioners Act 2020 (NSW) (DBPA), particularly within the framework of section 37 which establishes a statutory duty of care for individuals engaged in construction work. This term plays a pivotal role in determining the liability of construction professionals, yet the DBPA fails to provide a clear definition, leaving us to look to case law for guidance.

The Legal Framework

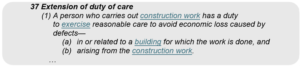

Under section 37 of the DBPA, individuals involved in construction work owe a statutory duty to exercise reasonable care to avoid economic loss caused by defects.

This duty extends to property owners (and subsequent owners) where construction work is carried out. Section 36(1) further broadens the scope of “construction work” to include tasks such as supervision, coordination, project management, and notably, “otherwise having substantive control” over how construction is carried out.

Defining “Substantive Control”

Although “substantive control” is not explicitly defined in the DBPA, courts have clarified its scope through the case law. Essentially, the courts have interpreted the term to mean the ability to control the execution of construction work, regardless of whether that control is actively exercised. In other words, liability under the DBPA can extend to individuals who can influence how work is carried out, even if they do not directly perform that work.

Key Case Law Interpretations

- Pafburn Pty Ltd [2022] NSWSC 659

The Pafburn case, at first instance, established that substantive control doesn’t require the actual exercise of control, but only the ability to control. Justice Stevenson highlighted that a person could be considered to have substantive control if they were in a position to influence how construction work was executed. This includes situations where a party has ownership or decision-making authority, such as a developer owning all the shares in a builder.

- Boulus Constructions Pty Ltd v Warrumbungle Shire Council [2022] NSWSC 1368

In Boulus Constructions, the Court affirmed that individuals with authority over key decisions—such as a managing director or site supervisor—could be deemed to have substantive control. Even without directly performing the work, these individuals were responsible for supervising, directing subcontractors and overseeing the project. The Court allowed Council to join these people to the proceedings.

- Oxford (NSW) Pty Ltd v KR Properties Global Pty Ltd [2023] NSWSC 343

The Oxford case further solidified that a person who oversees or influences the construction process—even if not physically involved—can still be considered to have ‘substantive control’. The court ruled that the sole director’s oversight and ability to influence work constituted substantive control, regardless of direct involvement.

- University of Sydney v Multiplex Constructions Pty Ltd [2023] NSWSC 383

This case clarified that issuing compliance certificates alone does not constitute substantive control. For a certifier to be liable, the claimant must demonstrate the actual ability to control or influence how the work was carried out, beyond merely certifying compliance.

Practical Implications

- Broader Liability: Individuals such as directors, project managers and site supervisors who have authority to influence construction work may be held liable under the DBPA, even if they don’t directly perform the work themselves.

- Factual Inquiry: Whether a person has substantive control is determined on a case-by-case basis. Factors like ownership structures, authority over decision-making and the ability to direct construction work are key in assessing liability.

- Certifiers and Substantive Control: Certifiers may face liability under the DBPA, but merely issuing certificates without any direct involvement or influence over the work is not enough to establish substantive control.

Conclusion

Understanding “substantive control” under the DBPA is essential for construction professionals, as it extends liability beyond those directly engaged in physical work. Key roles with decision-making authority, such as directors or project managers, may be held accountable for defects in construction work if they have the power to control how construction work is carried out. This broad interpretation of control ensures that those in positions to influence construction practices are held to account, contributing to higher standards in the industry.

For construction professionals, it is essential to understand how your role and authority can expose you to liability under the DBPA. Even if you are not directly involved in the physical work, you are still responsible for exercising reasonable care to prevent economic loss and defects. Your ability to influence how construction work is carried out places a significant duty of care on you to prevent economic loss caused by defects.

Bradbury Legal is a specialist building and construction law firm. If you or anyone you know requires advice or assistance, reach out to us on (02) 9030 7400, or email us at [email protected] to see how we can assist you.