This article is Part II of our article on ADR process. In this article, we will be covering the common pitfalls of ADR clauses. In Part I, we discussed the different types of ADR processes that are common in construction law matters. You can find Part I of our article HERE. While there are benefits to ADR processes, the drafting of dispute resolution clauses can sometimes result in the clause being void and unenforceable. Alternatively, there are times where the drafting of the dispute resolution clause means parties are left with a result under the contract which is unfair or unjust in the relevant circumstances. Often dispute resolution clauses are thrown into a contract without the parties giving much thought or consideration as to its enforceability or suitability to the circumstances. The following matters are pitfalls you should consider when you are drafting a dispute resolution clause.

Factors that may make the clause void and unenforceable:

Precondition to Court or other legal action

One of the biggest problems with ADR clauses arises when they set compliance with the ADR process as a pre-condition to seeking any court relief. This is problematic because it attempts to prevent the parties from approaching the Court when it has jurisdiction. If not properly drafted, these types of clauses can make the dispute resolution term unenforceable.

Words or phrases to look out for:

‘The parties must not seek any court orders until the parties have attended mediation.’

Words or phrases that can prevent the clause being unenforceable:

‘Nothing in this clause X prevents the parties from seeking urgent or injunctive relief from the Court.’

The key difference between these clauses is that the first tries to remove the jurisdiction of the Court by preventing the parties from seeking any relief from the Court until after the ADR processes have been complied with. This can result in some of the parties’ legal rights being wrongly enforced under the contract. For example, in cases where one party seeks to have recourse to security and the other party disputes this, the ADR process mechanisms may be too slow in resolving this dispute. Therefore, it is appropriate for the Court to be able to order urgent or injunctive relief to prevent recourse to the security. The parties can still have the underlying dispute proceed to the elected ADR process, but the security providing party may be able to (in the interim) prevent recourse where it is contested that the other party is not entitled to the benefit of that security.

Agreement to agree

A dispute resolution clause will be unenforceable if it is void for uncertainty. This often happens when there is an agreement to agree in a clause. For example, if a contract provides that the parties must agree on a matter and the parties are unable to reach an agreement, where do the parties stand in respect of their contractual duties? In the context of a dispute resolution clause, this can occur when the parties are required to agree on the form of the dispute process, or the appropriate body to determine the dispute or the rules that are to be applied to determine the dispute.

Words or phrases to look out for:

‘The parties must agree on an expert’ or ‘the parties must agree on the form of dispute process’

Words or phrases that can prevent the clause being unenforceable:

‘The parties must agree on an expert. If the parties cannot agree, the expert shall be appointed or administered by the [for example] Australian Disputes Centre.’

The important difference between the two clauses is the second has a mechanism for resolving the uncertainty. If the parties cannot agree on which expert should be appointed, the clause provides for a third party to appoint or determine who the expert will be. Obviously, when nominating a third party to make the decision, it is important to confirm that the third party can and will appoint a dispute resolution professional.

Time frames should also be included as part of these clauses to avoid uncertainty. For example, a clause may state that parties are given 14 days to meet together to discuss the dispute before it proceeds to mediation. Without the 14 day timeframe, there is no clear indicator of when the parties are to engage in their dispute resolution process. A deeming mechanism should also be included to account for when the parties simply do not comply with the dispute resolution process. For instance, if the parties do not meet within 14 days, then the dispute should be automatically referred to mediation, or expert determination (as per the next tier of the agreed dispute resolution process) or simply allowed to proceed to litigation.

Broad and unclear drafting

The last pitfall of dispute resolution clauses discussed in this article is broad and/or unclear drafting. As a general problem with contracts, broad and/or unclear drafting can result in less certainty in the obligations between the parties. In the context of a dispute resolution clause, unclear drafting may occur in any of the following circumstances:

- where there is not a clear process for a dispute to be resolved;

- where the scope of the ADR powers and what can they determine is not defined;

- where the rules that guide the ADR process are not clearly referenced; and

- when can parties appeal the decision.

The consequence of broad and/or unclear drafting is that when a dispute arises, further disputes may occur when it comes time to interpret the clause. If a Court considers that the clause is uncertain and is unable to be properly interpreted, it may be held that the clause is void for uncertainty.

To assist with some of the considerations that arise with broad or unclear drafting, the next section of this article gives commentary on some of the considerations of ADR clauses so as to ensure your clause is suited to the parties and properly drafted.

Important Considerations in ADR clauses

Scope of ADR power

A dispute resolution clause can be customised by the parties. One way that parties can customise their dispute resolution clause is by determining what types of dispute will be resolved in which ways. For example, the parties may agree that technical matters to do with the scope of works or variations are unsuited to a determination by a legal professional. In such technical matters, the Courts will often have to consider expert reports from both parties, including any updates and responses from the experts. Even after considering the expert reports, the Court may nevertheless be unequipped or unsuitable to determine exactly what the correct outcome is or should be. Methods such as expert appraisal or expert determination can be effective ways of the parties reducing their costs and ensuring an appropriate resolution of the dispute. If this method is agreed by the parties, it is important to clearly set out exactly which disputes are to be resolved in which way. For example, the dispute resolution clause may state that any dispute involving a disputed variation or defective work that hinges on a technical interpretation must be resolved through expert determination. Accordingly, such a clause would also express that any dispute that hinges on legal interpretation be directed to a court of competent jurisdiction.

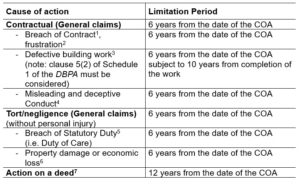

Statutory Provisions

When drafting a dispute resolution clause, it is important to consider whether there are any statutory provisions that may impact on the operation of the clause. For example, the Home Building Act 1989 (NSW) prevents the use of arbitration in some contracts for residential building work. In Victoria, the Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 2002 (VIC) has an intricate regime for claimable variations in high value contracts (being contracts with a consideration over $5,000,000). These statutory provisions can have significant impacts on the clauses chosen by the parties. Further, while the Home Building Act prohibits the use of arbitration, the Victorian Security of Payment Act has consequences for the parties depending on the type of resolution used. It is important then to consider the statutory provisions and what their effects may be.

Binding or non-binding

A major consideration that parties should think about is whether to have the dispute resolution process as a binding or non-binding method. The Courts have generally held that where parties agree to a binding dispute resolution process, they will be unable to appeal the determination. While there may be circumstances where the parties can appeal to have the determination overturned, as a general rule, parties should expect to be bound by the decision. Therefore, parties should consider when they want to be bound by the decision of the dispute resolution professional.

Rights of appeal

While the process may be binding, the parties may agree to allow for appeal rights in the dispute resolution clause. For example, the parties may agree that a decision can be appealed where a party claims there has been a manifest error of law or where the amount in dispute exceeds a specified threshold. These mechanisms are interesting ways that parties can customise their dispute process and ensure that they are satisfied with the way any potential disputes will play out. It is important to consider any cost implications with appeal rights. While parties may not wish to be bound by a decision in certain circumstances, appeal rights may inevitably lead to higher costs in resolving a dispute.